For several months, obscure tents, humidifiers, dehydrators and colorful jars have been alive with activity in the advanced culinary kitchen. I have been experimenting with fermented foods and intrigued by their powerful role in producing amazing levels of flavor.

From vinegars and black garlic to krauts, natto, koji and fermented juices, I am learning so much about the value of time and temperature and the life that these elements bring.

Fermentation is a strong player on the culinary scene. Restaurants such as Noma in Copenhagen are leading the revival and appreciation of an art that has been overlooked and forgotten until recently. In modern times, we are all aware of the impact of globalization. We can access foods from all over the world, out of season, under ripe and modified, processed and shaped to our needs and specifications. It is only in the last 10 years that we have begun to understand that this is at a detriment to our planet and the food that we are cooking.

Read more about Noma's Fermentation Lab.

Those inspirational chefs leading the culinary world are looking elsewhere for stronger culinary ethics and flavor, ridding themselves of the reliance of the energy-thirsty meat industry to take center stage on the plate and exclusively relying on the terroir from which they can harness. Using products in season and trusting ancient preserving techniques allows them to be creative with flavor and texture and brings a sense of belonging to the dishes they serve. It is only with great experimentation and self-education that these cooks have changed the way we extract flavor. With time, temperature and knowledge, we as cooks can now feel proud of the impression we leave with our customers and impact we have on our wider communities.

What is Koji?

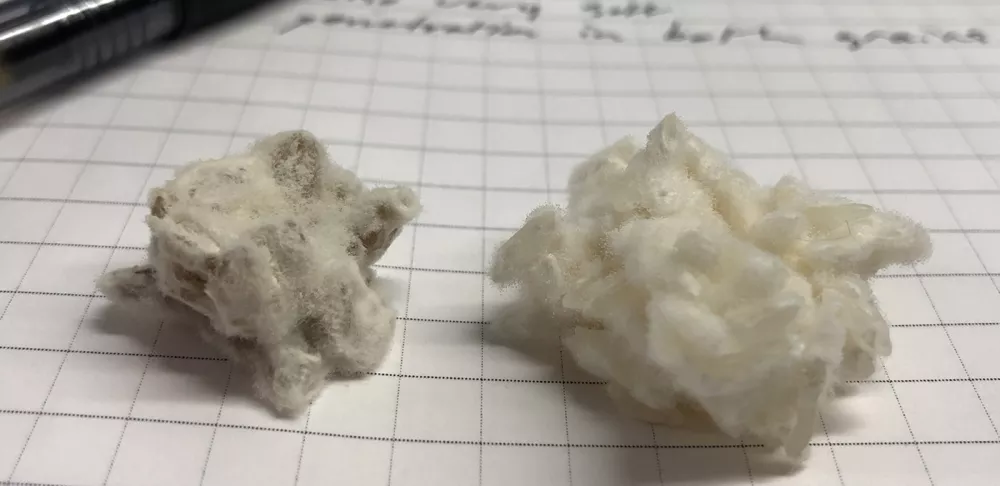

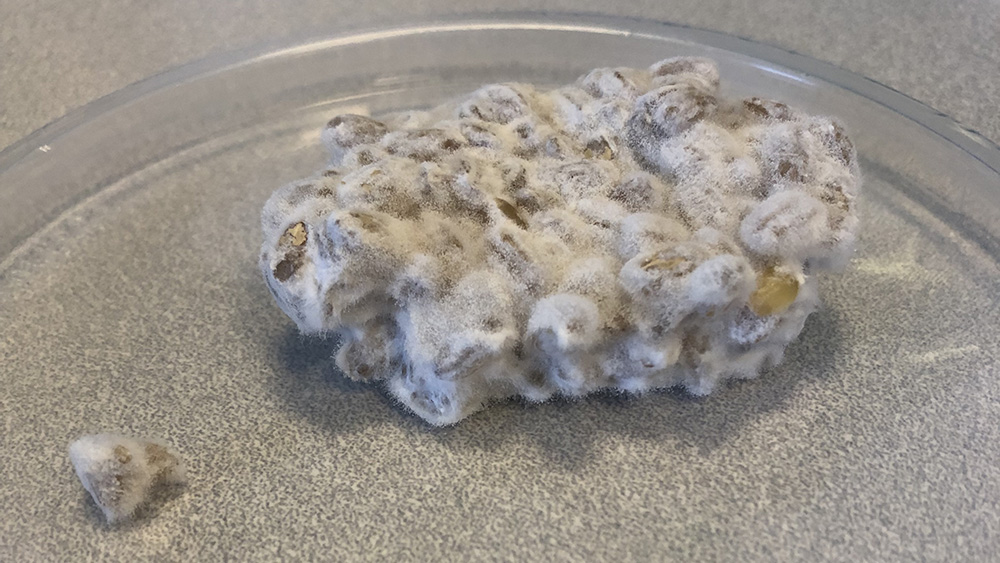

One of my first projects in fermentation was an exploration of koji production. Koji, or Aspergillus oryzae, is a sporulating mold that is introduced to grains of rice or barley; its penetration produces enzymes, converting starches in simple sugars. The inoculation of the grains, combined with the correct temperature and humidity, allows the fungus to sprout branching cells, also known as hyphae, almost like a plant root that digs deep into the grains. This spread meets with more branches until a mycelium network has been achieved, clumping the individual grains together in a fuzzy white blanket and causing a caking of the grains.

The end result is koji. Something that has been used for thousands of years around the globe, yet its use is only recently being introduced in western kitchens. This umami-rich product is changing the way we cook, providing a more effective and sustainable method of gaining rich and complex flavors without the laborious and expensive forms of flavor extraction used in traditional French cooking. These all-important enzymes released by the growth of the branching hyphae create an array of flavors: earthy with sweet and fruity notes.

Here are some notes from my recent experiments (fails and all):

Koji Rice Fermentation Test No. 1 (May 22): Initiated speed rack for fermentation incubation.

I began by transforming a speed rack into the correct holding environment for Aspergillus oryzae: a covered rack with a heating fan as a heat source at 15% power (heat element 2) and fan mark 6. To control humidity, I used a small household humidifier with 2.7 kilograms of water. A thermostat maintained the temperature at 30 C/86 F and a humidistat held to 75% humidity. Insulated blankets are placed at the foot of the rack to maintain temperature and humidity with little loss. Initial trials to hold temperature did not work sufficiently. The environment was modified, closing the space between the heating element and the top of the unit to minimize energy. The humidistat was overworking and therefore running out of liquid too quickly. Moving the shelves up in the rack and aiding in the insulation helped to maintain the correct environment.

Koji Rice Fermentation Test No. 1 (May 22): Initial Grain Inoculation

I decided to test a different set of grains in order to determine the best penetration and growth of the fungus. I began with 170 grams of barley, and long-grain and short-grain sushi rice. The grains were soaked for a full 24 hours until well hydrated, which aided for penetration of the hyphae.

- Barley increased weight by 83% absorbing 141 grams of H2O equaling 311 grams total weight.

- Long grain increased weight by 34% absorbing 57 grams of H2O equaling 227 grams.

- Short grain increased weight by 37% absorbing 63 grams of H2O equaling 233 grams.

Grains were then steamed until just tender but plump. Grains must be cooked enough to allow growth but not too wet as the Aspergillus oryzae will effectively drown in the moist environment.

- Barley cooked perfectly in as little as 10 minutes (due to increase of 83% weight in H2O).

- Long-grain rice did not cook well at all. (Long grain rice will be eliminated from this cooking method until a more consistent steam flow is found, i.e. steam combi oven.)

- Short-grain rice cooked in 30 minutes.

Grains were spread onto a tray and separated by hand. Keeping the grains whole and plump and removing excess starch will aid in branching. Grains were then inoculated with the Aspergillus Oryzae spores. A shaker with ground spores was shaken over the grains and mixed well.

- Barley is inoculated with 1:114 koji to grain ratio.

- Long grain is inoculated with 1:208 koji to grain ratio.

- Short grain is inoculated with 1:52.25 koji to grain ratio.

Grains are placed into a germination pad and onto the rack at 86 F and 75% humidity.

Koji Rice Fermentation Test No. 1 (May 22): Observation

- 24 hours: 84 F/78% - too early for detection, light mold spore growth/ environment stable.

- 36 hours: 86 F/75% - spores beginning to take shape.

- 48 hours: 85 F/76% - aroma very strong in unit, barley soft, good caking; short-grain rice soft, less caking. Long-grain not successful.

Koji Rice Fermentation Test No. 1 (May 22): Review

Germination tray is removed from environment and left to cool.

- Barley: great mold penetration, good caking. Strong fruity aroma, deep mushroom and peach-like flavor notes.

- Short-grain rice: good penetration (not as strong as barley), caking must be improved. Good aroma, flavor not as potent as needed.

- Long-grain rice: Nope! Penetration poor, caking poor, aroma non-existent, flavor not desirable.

Koji Rice Fermentation Test No. 1 (May 22): Conclusions

- After the first trials in koji production, results were mixed yet encouraging. Barley outperformed both rice grains by a significant degree.

- Flavor from the barley was exciting and exactly as required for further use. This barley was to be split up for spores (further fermented and dried) and to be infused in oil and used as a confit vehicle to help flavor and break down tough proteins.

- The rice grains need more work, initial reviews show that the steaming method may need to be adjusted to allow proper plump grains before inoculation.

This initial trial was interesting, educational and testing. At times I had to urge myself not to check every five minutes for growth (a watched pot never boils, you know)! Patience is key and now I can adapt this process to further trials until I have achieved three successful grains and am able to produce a larger volume.

My next blog post will feature a dish using a smoked koji oil made from barley.

See more from the Culinary Technology Lab and begin your culinary education.