My exploration into the art of fermentation has led me down a fascinating and winding path, intertwined with science, craft and cultural history, including most recently, a cooperage to learn more about barrel coopering's impact on the culinary world.

For hundreds of years, the human population has relied upon the talented hands of craftsmen to help shape the world in which we live today.

When humans began exploring the globe, trade, war and construction boomed. Global expansion and urban growth relied critically on the transport of supplies and commodities. Vessels for transportation became vital for the sprawling population of the developing Roman empire when huge quantities of goods were required to reach the military quickly. Although Romans are known for their roads, it was the shipping of goods across the water that provided the fastest and cheapest supply routes.

As early as 3 A.D., ships would be laden with clay vessels, filled with wine, spices, olive oil, silk, wheat, fish sauce, tin, gold and glass. Some ships would carry as much as 300 tons of cargo in a single journey. Heavy and fragile clay vessels often succumbed to the turbulence of sea travel so wooden barrels became a replacement. Caesar introduced wine to the Bordeaux region of France just as the Roman empire crumbled, transporting vast quantities of massive economic importance. A thousand years later, after the Battle of Hastings in 1066, trade flourished across the English Channel with 200 ships of wine cargo transported to England every year.

My initial questions for John Cox of Quercus Cooperage were, of course, what does a cooper do and what is their importance in the world of trading. “The wooden barrel was the cardboard box of its time,” explained Cox— from potable water, eggs, fish, and wine to glass, cotton, tobacco, cement and whaling oil — was being shipped and traded in barrels. The now precious vessels were instruments of economic growth, and the cooper became cherished for making, tending to and repairing them.

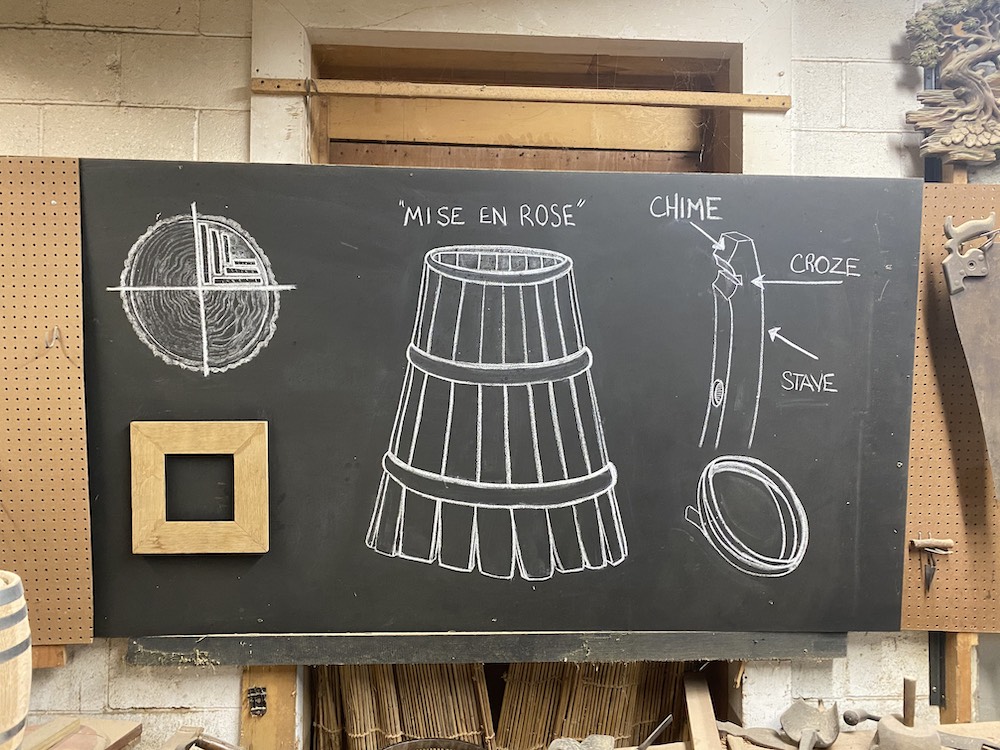

I visited John in High Falls, New York, to better understand his craft and its culinary applications. A cooper is someone who works with coopered joinery by attaching wood at a certain angle. One of 30 barrel coopers in the United States, John is one of a handful still using traditional methods.

John hand crafts beautiful barrels, fermentation vessels, tubs and kiokes and has recently designed and produced a custom muro and kioke for use in the culinary technology lab.

“I’m a cooper. I’m 5’6” — I’m considered a mini cooper,” he says. (We chuckle, it seems as if he’s said this before!). John began working with wood in his teens and after 28 years in the custom cabinetry industry, looked elsewhere to apply his passion and trade. Traditional barrel cooperage “just sucked me in,” he says.

So, what was a cooper and how has the craft changed over the last millennium?

John took advantage of an opportunity to meet a rise in demand for oak barrels from the craft spirit industry. Beyond that economic lure, it is clear to me in our conversations that he is preserving a trade that has so many cultural, economic and historical ties. John spent the next two years learning his craft by reverse engineering barrels. He fashioned modern tools based on 19th-century coopering tools found at a museum auction.

In my search for the perfect fermented foods, I also wanted to make sure I was using traditional methods and vessels to capture the full extent of microbes at work. John’s knowledge and passion for his craft has sparked my interest as I begin to unravel a whole world, which I did not know existed.

Coopering requires brains and brawn. A cooper must be physically strong and use math to calculate exact dimensions and angles. Coopered joinery works with an equation to find the angles needed to form a perfect joint. A picture frame, for example, takes the degrees in a circle (360), divided by the number of pieces of wood (four). The outcome (90), is then divided by two to find the angle needed to join the pieces together (45 degrees). The same works for a wooden barrel. A barrel with 36 pieces of wood is divided into 360, and then the result is divided by two to find the angle needed to join each piece of wood (5 degrees).

There are three types of coopers:

- A white cooper historically crafted utensils, bowls, pails, butter churns, spoons, ladles and other kitchen implements.

- A slack cooper fashioned slack barrels for transporting nails, glass, cement, dry goods and pelts.

- A tight cooper produces barrels for liquids, like water, wine, whiskey, milk, oil and paint.

American colonial industries relied heavily upon the barrel and the cooper for not only trade but also construction. In Jamestown, pipes were coopered to bring water inland from the James River. The Statue of Liberty’s construction relied on cement transported down the Hudson River from Rosendale, New York. The whaling oil industry relied so heavily on the craft that barrels were coopered on deck while whale oil was melted.

The barrel requires a bilge (the thickest part) in order for one person to move, pivot and lift it. Six riveted rings hold its shape, pushing the angled wood together to form a tight seal. The barrel is steamed to soften and loosen lignin (an organic polymer found in the cell walls of plants). The barrel is then toasted. (American distillers are federally mandated to use new charred oak barrels for aging whiskey.) Toasting the barrel develops the aggregate sugars, such as cellulose and hemicellulose, and produces flavors such as coconut, honey and vanilla. The last phase is charring: 1,300 F for 45 seconds changes the wood from toasted to blackened and charred, developing the color and flavor you taste and see in barrel-aged products like whiskey.

Such was the value of those tending to barrels or butts that we see the imprint in our culture today. Both were kept in the “buttery” (cellar) storing ale, wine and other liquids, and the person in charge of them became known as the “butler,” a highly regarded member of the household staff. At its peak, coopering was big business: John Rockefeller had the largest cooperage in the world when he became the largest producer of oil. In 1901, there were thought to be 91 million barrels in the United States, among a population of 93 million people.

However, just like the clay vessel, the wooden barrel met its decline. After the industrial revolution and prohibition, the shipping container, tin drum and corrugated cardboard replaced the barrel with lighter, cheaper and rapidly manufactured products. To this day the number of coopers is dwindling with industrial manufacturing replacing traditional methods of cooperage, and trade knowledge (traditionally passed down from generation to generation) has been lost along the way.

As other uses declined, only the alcohol industry has sustained the need for the cooper. In recent years, a surge in interest in craft spirits led to an increase in demand for oak barrels, an opportunity John realized. The requirements needed to produce a single barrel are exhausting, however. Barrels must use two to three-year air-dried white oak, not dried in a kiln. The lignin must be present and uncrystallized, and the wood quarter sawed so the grain is perpendicular to the barrel face, allowing the tubular cell structure to expand and prevent water from seeping through.

Now John’s expertise is in high demand from a growing community of fermenters. The level of skill and accuracy it takes to create a single barrel, tub or kioke leaves its imprints in everything we ferment, age and store. Fermentation vessels such as kioke, used for making shoyu and miso, are growing in popularity. I reached out to John in search of a white cedar muro (inoculation cabinet), and he designed a prototype that I use at ICE now. For 7,000 years, people have been making koji, but here in the U.S., it was nearly impossible to find trays, let alone the muro that is needed to house them, before this prototype.

In the lab, my ferments have the terroir of the fallen oak, still very much alive in the transformation of the final product. Microbes that proliferate on a substrate inside my cedar muro field their own microbiome. I ferment hot sauce in a charred oak tub, shoyu in a white cedar kioke and koji in white cedar trays.

In the food and beverage world, chefs and restauranteurs, brewers and distillers get most of the credit for the beautiful tastes that enhance our most precious life experiences and social interactions. Other trades, terroirs and cultures have a lasting impact on that taste. If you explore deep enough, you can unravel a truly fascinating story.

Explore fermentation in Culinary Arts, Pastry & Baking Arts, or Health-Supportive Culinary Arts at ICE.