Fermentation is founded on the effects of microbes in nature. In ancient civilizations, from Iran and Yemen to Saudi Arabia and North Africa, vats of grapes were seen “boiling” as microscopic yeasts broke down natural sugars into molecules of alcohol, of course not boiling at all, but bubbling under the action of yeast consuming sugar and excreting alcohol. Wine was discovered and with this, another twist in the magical work of bacteria, vinegar became a byproduct.

The first recorded wine vessel was found in modern-day Iran around 5,000 B.C. Mass consumption of wine and beer is evident in ancient civilizations surrounding the Middle East and the Nile Valley. Vinegar, on the other hand, was very much a byproduct, prized for its anti-microbial properties and ability to prevent spoilage among vegetables. Pickling became a cherished process, and vinegar became more valued.

Beer and wine were produced and consumed and yet, at this time, there was no knowledge of how to properly store these liquids. Alcoholic beverages left open to the air would transform into a distasteful brew of acidic wine, or vin aigre in French. At first the scourge of winemakers, soon vinegar making became an art unto itself and now is prevalent in diets across the globe.

Making vinegar is a two-step fermentation process. First, alcohol is formed from yeast consuming sugars within fruits and grains. The yeast consumes the natural sugars in the produce and excretes alcohol. This is what we refer to as alcoholic fermentation.

To transform alcohol into vinegar, oxygen and a bacteria of the genus Acetobacter must be present for the second step to take place, acetic fermentation. These bacteria are found in all organic produce that contains sugar, such as fruits and plant roots. A combination of these bacteria and an aerobic environment causes acetification and thus, vinegar.

Explore ICE's New York campus.

The conditions for a stable vinegar, however, are truly dependent on the initial alcoholic fermentation process. The concentration of alcohol, or alcohol by volume (ABV), strongly affects the amount of acetic acid required for the liquid not to spoil. An ABV of 5% will roughly convert to 4% acidity. A minimum of 4% acidity (the legal requirement) is required to prevent spoilage, 5% is a more reliable number (the standard). Titration is needed to calculate the number of grams of acetic acid per 100 ml of vinegar. Vinegars, such as wine and Balsamic Vinegar of Modena, tend to be around 6%, a high range for food vinegars. Any vinegars around 10% and higher will be used for cleaning and weed killing and are dangerous to consume or inhale, risking burning and respiratory problems.

How is vinegar made at home today? One can start with an alcoholic beverage, such as wine, and create an aerobic environment. Adding a mother or an unpasteurized vinegar starts the acetification process. A breathable material, such as cheesecloth or a towel, is often secured over the container of wine to allow for oxygen while preventing bugs and other bacteria from interfering with the process. The liquid is kept in a dark, fairly warm environment (77 F), untouched. For months, the Acetobacteraceae metabolizes alcohol into acetic acid and over time, the harshness reduces, producing an all-round mellow-flavored vinegar.

In my research and experimentation in making vinegar, I wanted to understand the whole process deeply. I have produced vinegar from leftover wine and beer but was compelled to start from scratch.

I started off with a number of fruit wines, from apple-scrap cider to pineapple and blackberry wine. I began with a very traditional, wild approach, simply adding sugar and water and allowing the mash to ferment anaerobically until I had visually noted the fermentation ceasing. I, of course, produced alcohol. The problem was, it wasn’t very good. The flavors were off, and the wild yeasts weren’t strong enough to take hold. I did experiment, even knowing the taste, to see how this would translate through the second fermentation. To no surprise, I had vinegar, but again, it wasn’t very good. I wanted good vinegar. So back to it.

I started off with a number of fruit wines, from apple-scrap cider to pineapple and blackberry wine. I began with a very traditional, wild approach, simply adding sugar and water and allowing the mash to ferment anaerobically until I had visually noted the fermentation ceasing. I, of course, produced alcohol. The problem was, it wasn’t very good. The flavors were off, and the wild yeasts weren’t strong enough to take hold. I did experiment, even knowing the taste, to see how this would translate through the second fermentation. To no surprise, I had vinegar, but again, it wasn’t very good. I wanted good vinegar. So back to it.

I found a good basic formula for fruit wines, adding water, sugar and turbo yeast to really kickstart the first fermentation process. It is crucial to bolster many of these fruits with sugar as they have low attainable ABV. Apples can produce up to 5-6% ABV whereas blueberries and blackberries only 2%, too low to attain a minimum of 4% acidity during the second phase. To attain a 7% ABV, 139 grams of sugar per liter is required. Therefore, when using a fruit like blueberries with a 2% attainable ABV, I would need to add an additional 100 grams per liter, to reach the correct amount of sugar for conversion.

The method is as follows:

Alcoholic Fermentation

- Wash and clean fruit, mash to a pulp.

- Add 1/3 volume of water.

- Add turbo yeast to specification per liter.

- Add pectinase to break down the fruit structure.

- Add sugar in two installments: 1/3 on day one and 2/3 on day seven.

- Calculate ABV to a desired 7%.

- If a higher ABV has been attained, dilute to 7%.

Acetification

- Strain mash.

- Heat liquid to kill yeasts.

- Cool and back slop with 20% unpasteurized vinegar or a mother of vinegar.

- Cover jar with cheesecloth.

- Leave for 2-3 months until flavor has mellowed.

- Test titration to ensure minimum 4% acidity.

- Strain again, bottle and store.

Using this process, I found the alcoholic fermentation to pick up very quickly indeed. I was keen to shake the mash regularly to avoid any unwanted bacteria from growing and taking hold, as well as using a fermentation lock to release gas. I measured the brix (percentage of sugar) every day, noting the level of sugar decreasing as the yeasts consumed them, converting to alcohol. Once a minimum of 7% ABV was achieved, the mash was then strained and heated to 70 C. This would kill any yeast left in the mash and any bacteria present. Unpasteurized vinegar is then added at 20% volume to enable the acetification. (Once I had secured a mother of vinegar through each trial, I was able to use that instead.)

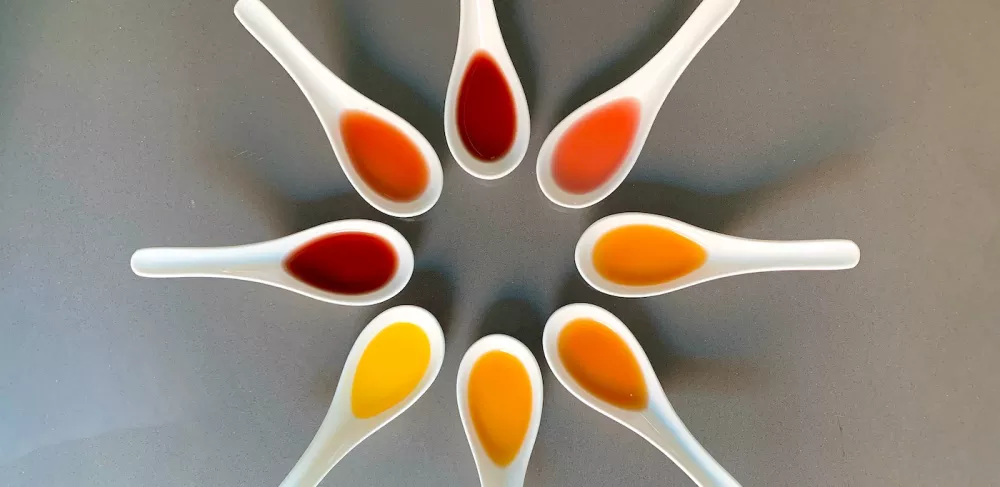

Between two and three months later, a well-rounded vinegar with a mellow, aromatic fruit flavor and a bright and tolerable acidity level was made. Each vinegar was poured off leaving any residual sediment at the bottom of the vessel, strained through cheesecloth and stored.

I am keen to dive back into wild ferments, in hopes to attain a good source of wild yeast to bolster the fermentation process, however the formula above proves a great method for solid results in color, flavor and character.

The world of vinegar offers insights into historic cultural developments and the world of preservation, so vital to the success of our species. Vinegars are a highlight of the fascinating microbial world in which we once so preciously relied upon and now offers a prized part of our culinary history.

Try more fermentation at home and explore food science in Culinary Arts.